Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are mental health conditions characterized by unhealthy eating habits and concerns about body weight or shape. Common types include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. These disorders can lead to serious physical and emotional health issues but are treatable with professional support.

Introduction

The behavioral problems known as eating disorders are defined by serious and continuous changes in eating patterns, together with the accompanying painful thoughts and feelings. These can be hazardous conditions that impair social, psychological, and physical functioning. Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, avoidant restrictive food intake disorder, other specific feeding and eating disorders, pica, and rumination disorder are among the several types of eating disorders.

When combined, eating disorders impact as much as 5% of the population and typically manifest in teens and early adulthood. All of these disorders can affect people of any age, but they are more prevalent in women, particularly bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Anxiety over eating or the effects of consuming particular foods, as well as obsessions with food, weight, or appearance, are frequently linked to eating disorders. Eating disorder-related behaviors include obsessive exercise, binge eating, purging by vomiting or abusing laxatives, and restrictive eating or avoiding particular foods. These actions may develop into compulsive habits that resemble addiction.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder, mood and anxiety disorders, and alcohol and substance use disorders are the most frequent mental conditions that co-occur with eating disorders. Although there is evidence that heredity and genes contribute to some people’s increased susceptibility to eating disorders, eating disorders can also affect people who have no family history of the problem.

Psychological, behavioral, dietary, and other health problems should all be addressed throughout treatment. The latter may include heart and gastrointestinal problems, as well as other potentially lethal diseases, as a result of starvation or purging activities. Anxiety about altering eating habits, hesitation toward treatment, or denial of an eating and weight problems are all typical. However, people with eating disorders can regain their emotional and psychological well-being and restart healthy eating habits with the right medical care.

Types of Eating Disorders

Anorexia Nervosa

Self-starvation and weight loss that results in low weight for height and age are hallmarks of anorexia nervosa. Aside from opioid use disorder, anorexia has the greatest fatality rate of any mental diseases and can be extremely dangerous. An adult with anorexia nervosa usually has a body mass index, or BMI, of less than 18.5, which is a measure of weight for height.

An extreme fear of gaining weight or becoming obese is what motivates dieting behavior in anorexics. Despite claiming to want and be striving to gain weight, some anorexics behave in ways that contradict their intention. For instance, they might exercise extensively and consume modest amounts of low-calorie foods.

Anorexia nervosa has two subtypes:

Restricting type: People who lose weight mostly through fasting, dieting, or overexercising.

Binge eating/purging type: This category includes people who occasionally engage in purging and/or binge eating.

Some of the following signs of starving or purging behaviors may appear over time:

- Menstruation stops

- Dehydration-related lightheadedness or fainting

- Brittle nails or hair

- Cold intolerance, weakness, and muscle weakness

- Reflux and heartburn (in vomiters)

- extreme abdominal pain, fullness, and constipation after eating

- Stress fractures are caused by obsessive activity, and bone loss results in osteopenia or osteoporosis (bone thinning)

- Fatigue, anxiety, depression, irritability, and poor concentration

Seizures, kidney issues, and irregular heart rhythms—particularly in individuals who use laxatives or vomit—are examples of serious medical concerns that can be fatal.

Restoring weight and normalizing eating and weight-control behaviors are key components of anorexia nervosa treatment. An essential part of the treatment strategy is the medical assessment and management of any co-occurring physical or mental health issues. The goal of the dietary plan should be to assist people in overcoming their eating anxiety and practice eating various foods with varying calorie densities at regular intervals. The best treatments for teenagers, young adults, and emerging adults include assisting parents in supporting and monitoring their children’s meals.

It’s equally important to address body dissatisfaction, although it frequently takes longer to address than eating and weight issues.

Admission to an inpatient or residential behavioral specialist program may be necessary for severe anorexia nervosa when outpatient treatment becomes ineffective. Although there is still a considerable chance of relapse in the first year after program discharge, the majority of specialty programs are successful in helping people regain their weight and return to regular eating habits.

Bulimia Nervosa

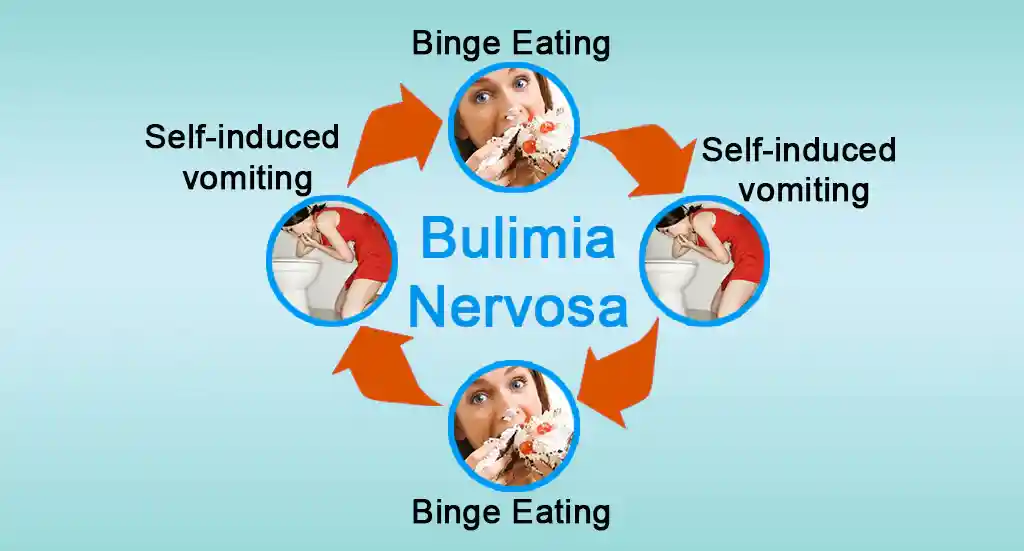

Bulimia nervosa sufferers usually alternate binge eating “forbidden” high-calorie items with dieting, or eating only “safe” low-calorie foods. Eating a lot of food in a short length of time while feeling out of control of what or how much one is eating is known as binge eating. Usually private, binge behavior is linked to sentiments of humiliation or shame. Food is frequently consumed quickly, past fullness, to the point of nausea and pain, and is high can be very substantial.

Every week or more, binges take place, usually followed by “compensatory behaviors” to avoid gaining weight. Fasting, vomiting, manipulating bowel movements, or obsessive exercise are a few examples.

Bulimia nervosa sufferers may be of normal weight, overweight, obese, or slightly underweight. However, individuals are classified as having anorexia nervosa binge-eating/purging type, not bulimia nervosa, if they are noticeably underweight. Because bulimia nervosa sufferers may not appear underweight and because their habits are concealed, family members and friends may not be aware that they have the disorder. A person may exhibit the following symptoms of bulimia nervosa:

- Frequently using bathroom facilities immediately following meals

- Large quantities of food going missing or mysteriously empty food containers and wrappers

- Persistent painful throat

- Swelling of the cheeks’ salivary glands

- Dental decay is caused by gastric acid damaging the enamel of teeth.

- Heartburn and reflux of the stomach

- Misuse of laxatives or diet pills

- Frequent, unexplained diarrhea

- Abuse of water medications or diuretics

- experiencing lightheadedness or fainting as a result of severe purging that dehydrates

Severe but possibly deadly side effects of bulimia include stomach rupture, esophageal rips, and severe cardiac rhythms. To detect and address any potential consequences, medical surveillance is important in situations with severe bulimia nervosa.

The most evidence-based treatment for bulimia nervosa is outpatient cognitive behavioral therapy. It assists patients in controlling the ideas and emotions that support their disease, as well as normalizing their eating habits. The impulse to overeat and throw up can also be decreased by antidepressants (such as fluoxetine). Young people with bulimia nervosa may benefit from eating disorder-focused family-based treatment, which includes educating relatives on how to help an adolescent or young adult regulate their eating habits.

Binge Eating Disorder

People with binge eating disorder, like those with bulimia nervosa, have fights of binge eating during which they eat a lot of food in a short amount of time, feel as though they have no control over their eating, and are upset about the binge behavior. However, they do not frequently engage in compensatory behaviors, such as vomiting, fasting, exercising, or abusing laxatives, to get rid of the food, unlike those who suffer from bulimia nervosa. Obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disorders are among the major health issues that can result from binge eating disorder.

Frequent binges (at least once a week for three months), a sense of helplessness, and three or more of the following characteristics are necessary for the diagnosis of binge eating disorder:

- Eating as quickly as usual.

- Consuming food until they get uncomfortable.

- Consuming a lot of food even while not hungry.

- Eating by themselves since they are ashamed of their excessive consumption.

- Feeling very guilty after a binge, dejected, or disgusted with oneself.

Individual or group-based cognitive behavioral psychotherapy for binge eating is the most successful treatment for binge eating disorder, just like it is for bulimia nervosa. Lisdexamfetamine, several antidepressant drugs, and interpersonal therapy have also been demonstrated to be beneficial.

Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder

Eating disorders or eating behavior problems that cause distress and affect social, familial, or professional functioning but do not fall under any of the other categories described below are included in this diagnostic category. Sometimes, this is because the weight requirements for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa are not fulfilled, or the frequency of the behavior does not reach the diagnostic threshold (for example, the frequency of binges in bulimia or binge eating disorder).

The eating and feeding disorder “atypical anorexia nervosa” is another example. This group includes people who may have lost a significant amount of weight and whose behaviors, obsession with weight or shape, and fear of being fat are typical of anorexia nervosa, but who, because of their baseline weight being above average, are not yet classified as underweight based on their BMI.

Despite appearing normal or above average weight, people with atypical anorexia nervosa who lose a lot of weight quickly by participating in excessive weight control behaviors may be at significant risk of medical consequences because the rate of weight loss is linked to medical difficulties.

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)

ARFID is a newly described eating disorder characterized by high selection and a continuous inability to achieve nutritional demands due to eating disturbances. One or more of the following factors may contribute to food avoidance or a restricted food repertoire in ARFID:

- Low appetite and disinterest in food or eating.

- Severe dietary avoidance based on food’s sensory qualities, such as texture, appearance, color, and fragrance.

- Fear of choking, nausea, vomiting, constipation, an allergic reaction, etc., are examples of anxiety or worry about the effects of eating. A major negative incident, such as a food poisoning or choking episode followed by a rising number of foods avoided, may trigger the disorder.

For someone to be diagnosed with ARFID, eating issues must be linked to one or more of the following:

- Significant weight loss (or children’s inability to gain the anticipated amount of weight).

- Substantial lack of nutrients.

- The requirement to maintain adequate nutrition intake through the use of a feeding tube or oral nutritional supplements.

- Disruption of social interactions (e.g., unable to share a meal).

The degree of starvation and the effects on mental and physical health can resemble those of anorexia nervosa. However, ARFID is different from bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa, and individuals with the illness do not have excessive concerns about their body weight or shape. Furthermore, although rigid eating patterns and sensory sensitivity are common in people with an autism spectrum disorder, these conditions may not always result in the degree of impairment necessary for an avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder diagnosis.

Food restrictions caused by a shortage of food availability, typical dieting, cultural customs like religious fasting, or developmentally typical behaviors like fussy eating in toddlers are all excluded from ARFID.

Commonly beginning in infancy or early childhood, food avoidance or restriction can last until adulthood. However, it can begin at any age. ARFID can influence families, increasing stress during mealtimes and other social eating situations, regardless of the age of the affected individual.

A registered dietitian nutritionist, a mental health expert, and other professionals may be included in the customized treatment plan for ARFID.

Pica

A person with pica, an eating problem, frequently consumes non-food items that are low in nutrients. The behavior is serious enough to require medical treatment and lasts for at least one month.

Common materials consumed include paper, paint chips, soap, fabric, hair, string, chalk, metal, stones, charcoal or coal, or clay, depending on the age and accessibility of the material. It is uncommon for people with pica to dislike food in general.

The behavior is not consistent with a culturally acceptable practice and is not appropriate for the person’s developmental stage. Although childhood onset is the most prevalent, pica can start in childhood, adolescence, or maturity. Children younger than that are not diagnosed with it.

For young children, putting tiny objects in their mouths is a typical developmental stage. Although it can happen to children who are otherwise typically developing, pica frequently co-occurs with autism spectrum conditions and intellectual disabilities.

Potential intestinal obstructions or harmful effects from substances taken (such as lead in paint chips) are risks for a person with pica.

Testing for nutritional deficits and treating them, if necessary, are part of the treatment for pica. Redirecting the person away from the nonfood things and rewarding them for putting them aside or avoiding them are two examples of behavior therapies used to treat pica.

Rumination Disorder

Rumination disorder is characterized by recurrent regurgitation and re-chewing of food after eating, in which food that has been swallowed is taken back into the mouth willingly and then either spat out or re-chewed. Infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood can all be affected by rumination problems. For the conduct to fit the diagnosis, it must:

- Occurs frequently for a minimum of one month.

- Not be brought on by a medical or gastrointestinal problem

- and not be a component of any of the previously mentioned other behavioral eating disorders.

- Rumination is also possible in other mental diseases (such as intellectual disability), but for a diagnosis to be made, it must be severe enough to require additional clinical care.

Symptoms and Causes

What symptoms and indicators are present in eating disorders?

Depending on the type, eating disorder signs and symptoms might include:

- Mood swings.

- Fatigue.

- Lightheadedness or fainting.

- Hair loss or thinning.

- Significant weight loss or unexplained weight change.

- Excessive sweating or heat flushes.

Among the behavioral signs of eating problems are:

- Eating restrictions.

- Consuming large quantities of food quickly.

- Avoiding particular foods or eating in general.

- Abuse of laxatives or forced vomiting after meals.

- Aggressive exercise after meals.

- Taking frequent bathroom breaks after eating.

- Avoiding social interactions or friends.

- Concealing or discarding food.

- Food rituals include eating in confidentiality and chewing food for longer than is necessary.

Because eating disorders frequently resemble dietary or lifestyle changes (adjustments to the things you do to change your general health), it may be challenging to identify one in a loved one. Additionally, you can’t tell if someone has the disease just by looking at them.

What is the experience of having an eating disorder like?

If you suffer from an eating disorder, you might experience:

- Food can be harmful or enemies.

- After eating, you did something improper or embarrassing.

- You don’t have the right physical size or weight.

- If you don’t satisfy specific dietary or weight requirements, you’re “failing.”

- You are seen badly by others.

- The only thing you can control in your life is what and how you eat.

- For fear of being judged, you don’t want to spend time with other people.

These emotions aren’t something you choose. An eating disorder has a significant negative influence on your decision-making, emotional stability, and social interaction skills in addition to your physical health.

What causes eating disorders?

It’s unknown what specifically causes eating problems. However, evidence indicates that eating disorders may be caused by several variables, such as:

- Genetics: Research has shown that binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa are hereditary. Your biological family may pass on genetic characteristics that increase your risk of contracting the disease.

- Brain biology: Your brain contains the neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine. They give you feelings of joy and contentment. These molecules may be activated during specific eating problem behaviors, according to research.

- Cultural and societal ideals: Pressure to “fit in” can have an impact on your mental health and cause you to adjust your behavior patterns to achieve particular, often unattainable, goals established by others. In the digital age, if you believe that you don’t look like the individuals you follow or admire, social media, television, and movies may also have an impact on your sense of self-worth.

- Underlying mental health problems: When you feel like you can’t handle other parts of your life, you might take drastic steps when it comes to food. A maladaptive coping mechanism for unpleasant emotions or feelings is an obsession with food. Because of this, certain eating problems coexist with other mental health problems.

Which variables increase the risk of eating disorders? An eating issue can strike anyone at any age. Teenagers and adolescents are most likely to have them. You might be in greater danger if you:

- Possess a biological family history of eating disorders or other mental health problems.

- Suffered from sexual, emotional, or physical trauma.

- Possess an underlying mental illness such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, sadness, or anxiety.

- Engage in sports like gymnastics, wrestling, or swimming, where your weight or body size matters.

- Go through a significant transition, such as moving, getting divorced, or starting a new work or school.

- Possess diabetes type 1. Up to 25% of women with Type 1 diabetes go on to develop an eating disorder, according to studies.

- Possess a strong will and follow excellence (perfectionism).

Which eating problems may give rise to complications?

Extreme activity, vomiting, or severe calorie restriction can all hurt your physical well-being. If left untreated, an eating disorder can lead to major problems like:

- Heart failure, arrhythmia, and further cardiac issues.

- Acid reflux (GERD, also known as gastroesophageal reflux disease).

- Digestive issues.

- Hypotension (low blood pressure).

- Brain injury, and organ failure.

- Osteoporosis.

- Severe constipation and dehydration.

- Halted infertility and menstruation cycles (amenorrhea).

- Stroke.

- Tooth injury.

Diagnosis and Tests

How are eating problems identified?

A medical professional will diagnose an eating disorder by:

- Doing a physical examination.

- Examining your symptoms again.

- Find out more about your exercise and food routines.

- Ordering imaging, blood, or urine tests (e.g., ECG, kidney function test) to rule out other potential causes of your symptoms or to assess for consequences.

Who makes the eating disorder diagnosis?

Eating disorders are diagnosed by medical professionals, such as doctors and mental health specialists. Your primary care physician might run blood tests, conduct a physical examination, and go over your symptoms. To find out more about your eating habits and views, a mental health counselor—such as a psychologist or psychiatrist—performs a psychological evaluation.

Management

What is the treatment for eating disorders?

Depending on the type of eating disorder, treatment options may include:

- Psychotherapy: The optimum kind of therapy for your circumstances might be decided by a mental health specialist. Family, group, and individual treatment are available. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a popular choice for those with eating issues.

- Medication: In addition to an eating disorder, you may also be suffering from anxiety or depression. These conditions may improve if antidepressants, antipsychotics, or other drugs are taken.

- Nutrition counseling: Creating healthy meal plans and enhancing eating habits can be facilitated by a certified dietitian with expertise in eating disorders. This expert can also advise on meal planning, grocery shopping, and cooking.

Combining several methods of treatment is frequently the best course of action. In order to address the condition’s behavioral, mental, and physical components, your care team will collaborate to develop a thorough treatment strategy.

A medical professional can assist you in managing food-related problems or other health disease even if you do not have a documented eating disorder.

Which degrees of care are available for eating disorders?

For eating disorders, there are many degrees of care, such as:

- Counseling once a week is known as outpatient treatment.

- Intensive outpatient treatment, which involves multiple sessions every week.

- Hospitalization for inpatient treatment.

- Together, you and your primary care physician will decide on the appropriate course of therapy.

Eating disorder therapy

In addition to being beneficial, therapy can also be difficult. A mental health specialist will meet with you regularly to help you understand and alter the thought patterns that influence your emotions and behaviors.

Being honest and genuine with a stranger is difficult. Accepting assistance might sometimes be challenging if you feel in charge of the circumstance. You might experience emotions and feelings in therapy that you might not want to consider.

Talking to your provider about these emotions is OK and even recommended. Know that your care team is here to support you at any time while you are receiving treatment.

Eating disorder recovery

The good news is that there is hope and that recovery is achievable. Eating problems take time to resolve. Therapy requires time. The severity and duration of your episodes will determine this. After beginning medicine or consulting a specialist, you might observe an improvement in your symptoms. Additionally, you may feel worse before getting better. This is typical.

Following the treatment plan prescribed by your healthcare practitioner is the best approach to recovery. Talk to them about any negative effects or difficulties you encounter. Keep your feelings open and honest. To assist you return to wellness more quickly, your doctors can provide tailored advice.

Prevention

Is it possible to prevent eating disorders?

Eating problems cannot be completely prevented.

You and your care team can identify and treat eating disorders and mental health concerns early if they run in your biological family. Unhealthy behavioral patterns can be broken with prompt treatment before they become more difficult to stop.

How can I reduce my chance of developing an eating disorder?

By seeking treatment for mental health problems (such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, and anxiety) and general health disorders as soon as symptoms appear, you may be able to lower your chance of developing an eating disorder.

The following may lower a child’s risk if you’re a parent or other caregiver and you know that eating disorders run in your biological family:

- Set a good example for others.

- Consume wholesome foods and refrain from referring to food as “good” or “bad.”

- Avoid discussing “dieting” with kids.

- Don’t criticize bodies in your remarks.

Prognosis

What does the future of eating disorders look like?

There is treatment for every kind of eating issue. For the best results, eating disorders should be identified early and treated immediately. It takes time to recover, and you might require ongoing assistance.

Eating disorders can be fatal if left untreated. See a healthcare professional for treatment if you or a loved one exhibits signs of an eating disorder.

FAQs

Are you suffering from an eating disorder?

Eating disorders are severe diseases that can have an impact on both your physical and mental well-being. Because your conduct seems so natural to you, you might not realize it is risky or destructive. You must get treatment if you believe you have an eating issue. You can recover with the right medical attention and mental health therapy.

Are eating disorders diagnosed based on certain criteria?

Because eating disorders are complicated, certain eating problems won’t fit the diagnostic mold. Everything needs to be treated seriously. If it’s time to assist, 36,37 can help. Who will be referred for assistance? Learn everything you can about eating disorders. Be outspoken about your worries. Be strong yet kind. From a doctor or therapist.

What occurs if treatment for an eating disorder is not received?

Serious side effects from an untreated eating disorder include heart failure, arrhythmia, and other cardiac issues. Acid reflux (GERD, also known as gastroesophageal reflux disease). Digestive issues. Hypotension (low blood pressure). Brain injury, and organ failure.

What is the treatment for eating disorders?

The sort of eating disorder you have will determine how you are treated, although talking therapy is typically part of the mix. If your physical health is being affected by your eating disorder, you could also require routine medical examinations. If you suffer from binge eating disorder or bulimia, part of your treatment may also include completing a guided self-help program.

What is another specific eating or feeding disorder?

Eating disorders of clinical severity that impair functioning but do not fit into any of the formal eating disorder categories are referred to as other defined feeding or eating disorders. Treatment is equally important for people with other specific eating or feeding disorders as it is for individuals with the officially recognized diagnosis mentioned above.

What is the prevalence of eating disorders?

Throughout their lives, 0.5 percent of women will suffer from anorexia nervosa, while 2-3 percent will suffer from bulimia nervosa. The most typical age range for onset is 12 to 25. 10% of cases found are in guys, although females are far more likely to have them. Since ARFID was only recently established, rates are unknown, and binge eating disorder and OSFED are more prevalent.

Which treatments work best for anorexia nervosa?

To normalize weight and eating habits, nutritional rehabilitation is a key component of anorexia nervosa treatment. The goals of psychotherapy are to manage difficult emotions and anxiety, stop relapses, and address unreasonable obsessions with weight and appearance. Among the interventions are tracking weight growth, recommending a healthy diet, and admitting patients who don’t gain weight to a partial hospitalization or specialty inpatient program. For patients who are unable to gain weight in outpatient settings, specialty programs that combine psychological therapy with close behavioral monitoring and meal support are typically quite successful.

Which treatments are successful in treating bulimia nervosa?

Although inpatient therapy is sometimes recommended, the majority of simple instances of bulimia nervosa can be managed outpatient. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, which includes self-monitoring of eating disorder-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, is the best psychological treatment. Finding environmental triggers and illogical beliefs or emotional states that lead to overeating or elimination, as well as normalizing eating behavior, are the main goals of therapy. Patients receive instruction on how to question illogical notions about their weight and self-worth. It has also been demonstrated that some drugs can effectively reduce bulimia sufferers’ purging and bingeing tendencies.

What about treatment for other eating disorders, such as BED, ARFID, and OSFED?

The most effective treatment approaches for eating disorders, which are behavioral issues, all center on normalizing eating and weight-control habits while controlling uncomfortable emotions and thoughts. Eating disorders are becoming recognized as learning and habit disorders as well as psychological issues. It might be difficult to break long-standing habits, but practicing healthy eating under professional therapeutic supervision helps build the skills necessary to control worries about food, weight, and appearance. These worries eventually go away as recovery becomes more and more mastered.

Reference

- Eating disorders. (2025, February 17). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4152-eating-disorders

- What are Eating Disorders? (n.d.). https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders

- Rd, A. P. M. (2024, June 11). 6 Common types of eating disorders (and their symptoms). Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/common-eating-disorders

- Frequently asked questions about eating disorders. (n.d.). Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/psychiatry/specialty-areas/eating-disorders/faq