Sarcopenic Obesity

What is a Sarcopenic Obesity?

Scropenic obesity is a consequence of integrating the two conditions which include obesity and sarcopenia. Obesity is defined by a body mass index (BMI) that is characterized by high body fat or being overweight, while sarcopenia is the loss of muscular mass, strength, and physical function that comes with aging.

As humans age, they are more likely to develop sarcopenic obesity, which has negative health effects. In addition to expediting the loss of muscle mass and function as previously mentioned, this condition is especially concerning for the elderly because of its compounding effects on mobility and general health.

The number of persons over 65 who have been diagnosed with sarcopenic obesity has grown. There is a correlation between sarcopenia’s loss of muscle mass, strength, and physical function and obesity’s high body fat because aging and a sedentary lifestyle can result in greater inactivity, which raises body fat levels and causes weight gain.

Asian guys had the highest rate of sarcopenic obesity, at 14.4%. Consequently, a consensual classification of sarcopenic obesity and its clinical significance is desperately needed. Future retrospective research studies could provide more powerful evidence and clarify statistical data because there is a lack of further data among various demographics. This does not, however, rule out a connection between the two illnesses or rule out the likelihood of related symptoms and/or health issues.

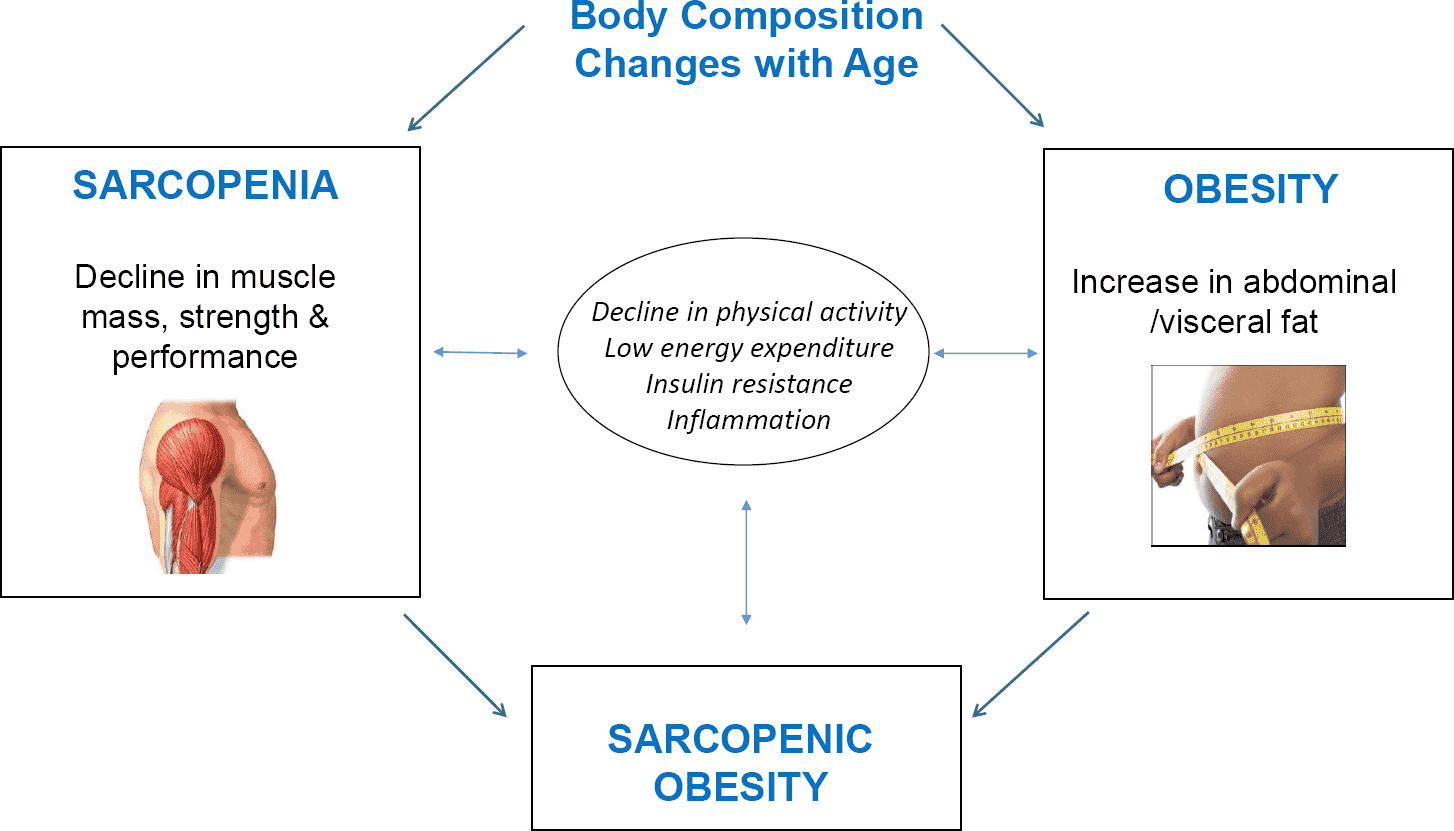

Pathogenesis

Several factors contribute to the pathophysiology of sarcopenic obesity, such as age, inactivity, vitamin imbalances and malnutrition, insulin resistance, and hormonal alterations that result in changes in body composition. Although the precise pathogenesis is unclear, these factors have been investigated for the development of sarcopenic obesity. These factors decrease anabolic hormones, physical activity, and metabolic rate while increasing insulin resistance and ectopic/omental fat deposition.

The protein/cytokine GDF15 and FGF21, which are indicators for cell damage and inflammation in response to stress, are believed to be elevated in sarcopenic obesity. There is also an increase in myostatin. In addition to immune cell buildup, obesity increases lipotoxicity and chronic inflammation.

Myosteaosis (fat buildup in skeletal muscles), oxidative stress (an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants that damages cells), mitochondrial malfunction, and anabolic resistance (less muscle contraction relative to protein) can all happen in the muscle.

In general, white adipose tissue expands into muscle tissue as a result of the cycle of adipose and muscle tissues. This stimulates other mechanisms, such as insulin resistance, and inhibits protein synthesis, which leads to a decrease in muscle mass. In addition to inhibiting insulin synthesis, the release of cytokines also raises the risk of disease through other pathways, such as cardiovascular problems that shorten your lifespan and raise mortality risk.

Symptoms of Sarcopenic Obesity

The symptoms reflect those of obesity and sarcopenia. Even though the person’s body mass index is healthy and adequate for their age, they will appear overweight.

Progressive diminution of muscle is an indicator of sarcopenia. Common symptoms of this illness include decreased walking speed, decreased stamina, imbalance with an elevated risk of falls, difficulties with daily tasks, trouble ascending stairs, and muscle atrophy.

Obesity is a component of sarcopenic obesity. Obese people have a variety of symptoms, such as trouble breathing, back and joint pain, a restricted capacity to engage in physical activities, snoring, frequent weariness, and excessive sweating. A variety of comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, dementia, fractures, diabetes, and even some types of cancer, can coexist with sarcopenic obesity in certain patients.

When someone develops sarcopenic obesity, their pre-existing diseases may sometimes get worse. Obesity can affect a person’s mental health in addition to their physical health. These include low confidence, which manifests as uncertainty, worry, and hesitancy when doing duties or being assigned to them. Obese people also frequently have low self-esteem.

Causes of Sarcopenic Obesity

The main causes of sarcopenic obesity include changes in body composition carried on by aging, hormone fluctuations, a poor diet lack of exercise, and other illnesses.

Aging

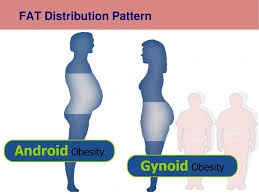

Aging is the main factor producing alterations to body composition. They are primarily characterized by a decrease in exercise and a lower basal metabolic rate, which can also be linked to increases in total fat mass, decreases in peripheral subcutaneous fat, and declines in muscle strength. Age-related hormonal changes can contribute to other alterations in muscle composition.

Hormonal Changes

Extreme adipose tissue growth brought on by both an increase in consumption and a decrease in energy expenditure is a common definition of obesity. Inflammation is another consequence of obesity that contributes to insulin resistance. Because it controls the expression of albumin and myosin and enhances the intracellular uptake of short-chain amino acids, insulin has a significant impact on protein synthesis.

Control of protein breakdown is also aided by insulin’s regulation of enzymes in the liver and muscles. Consequently, in skeletal muscle, insulin resistance may result in a decrease in protein synthesis and an increase in protein breakdown.

Reduced levels of testosterone, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and other anabolic hormones can also result from obesity. The generation of growth hormone is also inhibited by the high levels of free fatty acids in the blood. Loss of muscular mass and strength is frequently linked to these hormonal changes.

Inflammation

Inflammation is a major factor in the decrease in muscle mass and strength among people with sarcopenic obesity. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1) and adipokines (lectin and adiponectin) are among the hormones and proteins secreted by adipose tissue.

The inflammatory response is up-regulated in obese people because they have more adipose tissue. A decrease of strength and mass in the skeletal muscle may be an outcome of insulin resistance carried on by this inflammation. Additionally, by inhibiting protein synthesis and causing protein degradation, inflammation can directly result in muscular atrophy. During the development of metabolic problems in the liver, digestive tract, and other cells, it affects muscle mass.

Exercise

A decrease in physical activity, frequently brought on by aging, is one of the causes contributing to sarcopenic obesity. Muscle mass and strength decline as a result of this reduction in exercise. As a result, the basal metabolic rate drops, which permits more fat to accumulate. Lack of exercise, along with other variables, makes it harder for people to maintain exercising as their bodies age. likewise, insufficient exercise may influence hormonal balances and result in reductions in muscle protein synthesis.

Diagnosis

Low body mass index and excessive body fat are combined to form sarcopenic obesity. can be identified using metrics like the waist-to-hip ratio.

The presence of elevated adipose tissue with below-average muscle mass and function in a patient is known as sarcopenic obesity. An individual must go through some composition tests as part of the diagnostic process for sarcopenic obesity. Sarcopenic obesity tends to be underdiagnosed in all populations and is a little harder to identify than other diseases.

Given that people tend to lose muscular mass as they age, this ailment is believed to primarily afflict the elderly. Additionally, older adults are less likely to be physically active, which might contribute to weight gain. It is believed that the complex diagnosis of sarcopenic obesity leads to underdiagnosis, particularly among younger individuals. According to some research, the most effective method of diagnosing sarcopenic obesity is an anthropometric diagnosis based on South Asian cutoffs.

Human measurements are known as anthropometric measures. This approach to diagnosis entails non-invasive, measurable bodily measures. Height, weight, body mass index (BMI), head circumferences, skinfold thickness, and waist, hip, and limb circumferences are the measurements. The World Health Organization (WHO) or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) establish normal values based on an assessment of nutritional status, and those with abnormal levels are further evaluated.

Treatment of Sarcopenic Obesity

There are currently no treatments that can directly treat sarcopenic obesity. However, there are a few tactics that can be used to control both disease states, such as pharmaceutical and lifestyle changes. The condition of the patient can be improved with the aid of a suitable weight training and weight loss program.

Weight Loss + Exercise

Weight loss is possible with a minimum 10% calorie limitation. However, weight loss by dietary modifications may result in a decrease in body mass index and muscle mass, which worsens the symptoms of sarcopenia. Frequent exercise has been demonstrated to boost muscle strength and decrease muscle mass loss when combined with dietary modifications.

By promoting muscle protein synthesis and inducing muscular growth, increasing resistance exercise may help reverse sarcopenia. Exercise that incorporates elastic resistance training has also been demonstrated to promote weight loss and muscle atrophy.

Patients should incorporate this into their prescription if they want to reduce weight without sacrificing muscle mass. Muscle strength rose as body mass fell in patients who successfully lost weight and exercised, suggesting that muscle mass had grown.

Nutrition

A person’s diet, level of physical activity, and body composition all affect how much muscle mass they lose as they age. inversely, protein is an essential macronutrient for muscle growth. Even though protein is a crucial part of a healthy diet, older patients begin to lose their capacity to build muscle through the consumption of protein and amino acids.

Research also shows that even if older patients increase their protein intake, their ability to build muscle mass does not increase in comparison to younger patients. Elderly individuals should instead concentrate on eating high-quality protein that contains the amino acid leucine.

It is important to ingest the right amount of protein to avoid muscle mass loss because sarcopenic obesity is most common in older people. Supplementing with vitamin D, magnesium, and selenium may also help build muscle.

Myostatin Inhibitors

Muscle cells contain a protein called myostatin, which prevents muscles from growing. Myostatin is known to be present in larger concentrations in older patients than in younger ones, which increases the risk of sarcopenia. It might decrease the rate of muscle breakdown by blocking this protein.

Compared to mice who did not take myostatin inhibitors, older mice who received these medications had denser muscles and lower fat levels. They propose that lowering myostatin levels in the elderly may reduce the risk of sarcopenia, diabetes, and heart disease. There is little and continuous study on people, although the majority of evidence for animals appears encouraging.

Testosterone

Male diseases like obesity, sarcopenia, and cardiovascular hazards are associated with lower-than-normal testosterone levels, which are significantly lower in older people than in younger people. One study revealed that testosterone enanthate injections improved muscle mass in both younger and older individuals receiving testosterone therapy, while another study found that testosterone patches reduced fat mass in older males over 65. This kind of medication is not the only option for treating sarcopenic obesity; it also depends on the male patients’ serum testosterone levels.

Complications/Conclusions

Obesity and low muscle mass are risk factors for a decline in physical ability and life quality.

The risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, fractures, disability, and overall quality of life are all impacted by sarcopenic obesity. Because it is linked to all-cause mortality, this is significant. Taking preventative measures to postpone muscle deterioration and weight/fat control may be helpful in the case of an early diagnosis.

Preventative measures to lower the likelihood of sarcopenic obesity include a high-protein diet and outdoor exercise. Mitigating the controllable risk factors—malnutrition vitamin imbalances and a lack of physical activity—can enhance results. Although they have drawbacks, physical activity, and appropriate nutritional supplements are two crucial non-pharmacological ways to prevent and/or treat sarcopenic obesity. Muscle growth beyond age may be restricted if the person is unable to walk, has limited walking ability, or cannot perform higher-intensity exercise.

FAQs

Why does sarcopenic obesity take place?

‘Sarcopenic obesity’ may occur as a result of low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, excessive energy consumption, physical inactivity, and hormonal abnormalities.

How to diagnose sarcopenic obesity?

Assessment of skeletal muscle function should be the first step in the diagnostic process. This should be followed by an evaluation of body composition, where the diagnosis of SO is verified by the presence of excess adiposity and low skeletal muscle mass or related body compartments.

What are the symptoms of sarcopenia?

Muscle weakness.

Slow walking.

Trouble performing daily activities.

Trouble climbing stairs.

Which risks could sarcopenic obesity present?

While some studies indicate that sarcopenic obesity may have weaker cardiovascular function, recent cross-sectional and cohort studies indicate that sarcopenic obesity, as measured by muscle strength rather than muscle mass, is associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular mortality.

How is sarcopenic obesity measured?

Based on the geriatric notion of sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity is the presence of obesity (defined either by adiposity levels or by a BMI > 30 kg/m2) with changed body composition of the greater part of the skeletal system’s muscle and its impaired efficiency.

Reference

- Donini, L. M., Busetto, L., Bischoff, S. C., Cederholm, T., Ballesteros-Pomar, M. D., Batsis, J. A., Bauer, J. M., Boirie, Y., Cruz-Jentoft, A. J., Dicker, D., Frara, S., Frühbeck, G., Genton, L., Gepner, Y., Giustina, A., Gonzalez, M. C., Han, S., Heymsfield, S. B., Higashiguchi, T., . . . Barazzoni, R. (2022). Definition and Diagnostic Criteria for Sarcopenic Obesity: ESPEN and EASO Consensus Statement. Obesity Facts, 15(3), 321. https://doi.org/10.1159/000521241

- Wei, S., Nguyen, T. T., Zhang, Y., Ryu, D., & Gariani, K. (2023). Sarcopenic obesity: epidemiology, pathophysiology, cardiovascular disease, mortality, and management. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1185221

- Prado, C. M., Batsis, J. A., Donini, L. M., Gonzalez, M. C., & Siervo, M. (2024). Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: a clinical overview. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 20(5), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-023-00943-z

- Sarcopenic obesity. (2024, December 1). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarcopenic_obesity