Where Is Abdomen Located?

Introduction

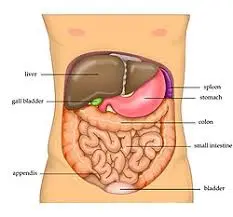

The abdomen is the area of the body between the chest and the pelvis. It houses vital organs like the stomach, liver, intestines, and kidneys, playing a key role in digestion, metabolism, and other essential functions.

The abdomen (commonly known as the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach is the anterior portion of the torso located between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and other vertebrates. The region inhabited by the abdomen is termed the abdominal cavity. In arthropods, it refers to the posterior region of the body, following the thorax or cephalothorax.

In humans, the abdomen extends from the thorax at the thoracic diaphragm down to the pelvis at the pelvic brim. The pelvic brim runs from the lumbosacral joint (the intervertebral disc located between L5 and S1) to the pubic symphysis and marks the edge of the pelvic inlet. The space above this inlet and beneath the thoracic diaphragm is called the abdominal cavity. The boundary of this cavity is formed by the abdominal wall in the front and the peritoneal surface at the back.

In vertebrates, the abdomen constitutes a significant body cavity enclosed by abdominal muscles at the front and sides, while part of the vertebral column forms the rear. The lower ribs also encase the ventral and lateral aspects. The abdominal cavity connects with, and is positioned above, the pelvic cavity.

It is linked to the thoracic cavity via the diaphragm, through which structures like the aorta, inferior vena cava, and esophagus pass. Both the abdominal and pelvic cavities are lined with a serous membrane called the parietal peritoneum, which is continuous with the visceral peritoneum that encloses the organs. The abdomen in vertebrates accommodates numerous organs associated with the digestive system, urinary system, and muscular system.

The belly (abdomen) is the body’s largest space (cavity). It is situated between the chest and pelvis and houses many of the body’s organs, including the liver, stomach, and intestines.

The groin is the section of the body where the upper thighs intersect with the lowest part of the abdomen. Generally, the abdomen and groin are separated by a muscular and tissue wall. The only openings in the wall are small channels known as the inguinal and femoral canals, which permit nerves, blood vessels, and other structures to transit between these two regions.

Surface

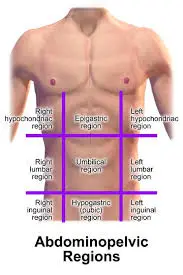

From an anatomical perspective, the abdomen is divided to enable clinical evaluation and localization:

Four Quadrants – Formed by the median sagittal plane and the transumbilical plane, leading to the right upper, left upper, right lower, and left lower quadrants.

Nine Regions – Defined by two horizontal planes (subcostal and intertubercular) and two vertical midclavicular planes, creating the right and left hypochondriac, epigastric, right and left lumbar (flank), umbilical, right & left iliac (inguinal), and hypogastric (pubic) zones.

Abdominal planes

The anatomic planes of the abdominal wall consist of multiple muscular and fascial layers that interdigitate and merge to create a resilient, protective musculofascial layer shielding the visceral organs while providing strength and stability to the trunk of the body. This anatomy varies concerning different topographical regions of the abdomen; therefore, a comprehensive understanding of these layers, their blood supply, and innervation is crucial for surgical management concerning the abdomen.

The abdominal cavity is the largest space within the body, bounded cranially by the xiphoid process of the sternum and the costal cartilages of ribs 7-10; caudally by the anterior ilium and the pubic bone of the pelvis; anteriorly by the musculature of the abdominal wall; and posteriorly by the L1-L5 vertebrae.

Imaging techniques have enhanced our understanding of key abdominal planes:

Transpyloric Plane – Situated between the lower edge of L1 and upper L2 vertebrae in most individuals, this plane crosses important structures such as the superior mesenteric artery, portal vein formation, left renal hilum, and the tip of the ninth rib.

Subcostal Plane – Usually aligned with the lowest bony point of the rib cage, it encompasses the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery.

Supracristal Plane – Located at the L4 vertebral level, frequently used in clinical settings to identify lumbar puncture sites.

Structure and Function

The abdomen ultimately functions as a cavity designed to house essential organs of the digestive, urinary, endocrine, exocrine, circulatory, and parts of the reproductive system.

The anterior wall of the abdomen consists of nine layers. From the outermost to the innermost, they are skin, subcutaneous tissue, superficial fascia, external obliques, internal obliques, transversus abdominis, transversalis fascia, preperitoneal adipose and areolar tissue, and the peritoneum.

The peritoneum is a single continuous membrane; however, it is classified as either visceral (lining the organs) or parietal (lining the wall of the cavity). Consequently, a peritoneal cavity is created and filled with extracellular fluid that serves to lubricate surfaces to minimize friction. The peritoneum consists of a layer of simple squamous epithelial cells.

The subcutaneous layer of the anterior abdominal wall below the umbilicus divides into two separate layers: the outer fatty layer referred to as Camper’s fascia, and the inner membranous layer known as Scarpa’s fascia. This membranous layer continues downward as Colles fascia in the perineal area.

The actual abdominal cavity includes the stomach, the first part of the duodenum, the jejunum, the ileum, the liver, the gallbladder, the tail of the pancreas, the spleen, and the transverse colon.

The back wall of the abdominal cavity is called the retroperitoneum. Structures located retroperitoneally include the adrenal glands, aorta, and inferior vena cava, segments 2 to 4 of the duodenum, the head and body of the pancreas, ureters, descending and ascending colon, kidneys, thoracic esophagus, and rectum. The mnemonic SAD PUCKER can be used to remember these structures.

Embryological Development

The abdomen originates from three primary germ layers during embryonic development. These comprise the ectoderm, which forms the outer skin, the somatic and splanchnic mesoderm, responsible for the abdominal wall’s skeletal muscle and the bowel’s smooth muscle, respectively, and the endoderm, which forms most of the digestive tract.

In terms of embryological development, the gastrointestinal system evolves into the foregut, midgut, and hindgut.

Foregut: extends from the esophagus to the proximal duodenum where the bile duct enters.

Midgut: spans from the distal duodenum to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon.

Hindgut: encompasses the distal third of the transverse colon down to the anal canal above the pectinate line.

Vascular Supply and Lymphatic System

The primary blood supply of the central abdominal wall comes from the superior epigastric artery (a branch of the internal thoracic artery) above the umbilicus, and the inferior epigastric artery (a branch of the external iliac artery) below it. Venous drainage is facilitated through the internal and lateral thoracic veins above the umbilicus, and via the superficial epigastric vein (branching from the femoral vein) and inferior epigastric vein (branching from the external iliac vein) below the umbilicus. Lymphatic drainage above the umbilicus primarily goes to the axillary lymph nodes but also drains some into the parasternal lymph nodes. Below the umbilicus, lymph flows to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Internally, the abdomen houses two major blood vessels— the aorta and the inferior vena cava. The aorta has three major branches that supply the gastrointestinal organs: the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries. These arteries branch off the aorta anteriorly, while arteries supplying non-GI structures branch laterally or posteriorly. Examples include the renal and gonadal arteries.

The blood supply to the gastrointestinal tract corresponds with the regions of embryonic gut:

The celiac artery supplies the foregut.

The superior mesenteric artery supplies the midgut.

The inferior mesenteric artery supplies the hindgut.

It is worth noting that the splenic flexure is a “watershed” region due to its dual blood supply from distal artery branches, which can lead to colonic ischemia.

Venous drainage from digestive organs goes through the portal system, while non-digestive venous drainage is channeled through the inferior vena cava and its branches.

The portal venous system is composed of the superior mesenteric vein, inferior mesenteric vein (along with the superior rectal vein), and splenic vein along with its branches, which all converge to form the portal vein. The ligamentum teres contains the remnant of the umbilical vein and is clinically significant for its link between the portal system and the abdominal wall. In cases of portal hypertension, patients may develop dilation of the periumbilical veins, referred to as caput medusae. Additionally, gastrointestinal cancers may spread to the anterior abdominal wall via the lymphatics that parallel the venous drainage, known as the Sister Mary Joseph sign or nodule.

Nerves

Key dermatomes to remember are the xiphoid process at T6, the umbilicus at T10, and the umbilical fold at L1.

The abdominal wall’s skin and muscles are innervated by the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the thoracoabdominal nerves (T7-T11), the subcostal nerve (T12), the iliohypogastric nerve (L1, providing sensation to the suprapubic area), and the ilioinguinal nerve (L1, supplying sensation to the ipsilateral medial thigh and scrotum).

From a visceral perspective, the vagus nerve is responsible for parasympathetically innervating the majority of the gastrointestinal tract, including the foregut and midgut. The hindgut receives its parasympathetic input from the sacral roots S2, S3, and S4.

Sympathetic innervation for the foregut is provided by the greater thoracic splanchnic nerve, while the midgut is supported by the lesser thoracic splanchnic nerve. It’s crucial to note that the visceral peritoneum and the underlying organs lack sensitivity to touch, temperature, or laceration; instead, they perceive pain through stretch and chemical receptors. Due to the way organs are innervated, pain is not well-localized and refers to the dermatomes of the spinal ganglia that provide sensory fibers.

As a result, pain from the foregut is typically referred to the epigastric region, midgut pain is felt at the umbilicus, and hindgut pain is experienced in the pubic area.

What are abdominal muscles?

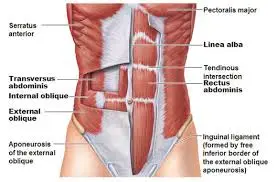

The abdominal muscles are robust bands of muscle that line the walls of your abdomen (the trunk of your body). They are situated at the front of your body, between the ribs and pelvis. These muscles serve many critical functions, such as supporting your trunk, aiding in movement, and keeping your organs securely in place.

The five primary muscles in your abdomen are:

- Rectus abdominis.

- Pyramidalis.

- External obliques.

- Internal obliques.

- Transversus abdominis.

Along with your back muscles, your abdominal muscles form your “core.” They play a key role in protecting your spine and maintaining stability and balance in your body.

Function

What are the roles of your abdominal muscles?

Your abdominal muscles have a variety of important functions:

- They stabilize your trunk and maintain consistent internal pressure within your abdomen. When increased pressure is required—such as during essential bodily functions like breathing, defecation, coughing, vomiting, and childbirth—these muscles regulate that pressure.

- They assist in the movement of your body between your ribcage and pelvis, allowing your trunk to remain in constant motion. This helps support your spine and trunk while walking, sitting, standing, or twisting from side to side.

- They keep your internal organs properly positioned and offer protection to them. This includes the stomach, intestines, pancreas, liver, gallbladder, and other organs.

- They help maintain your posture and provide essential core support.

Anatomy

Where are your abdominal muscles found?

Your abdominal muscles are situated between your ribcage and pelvis at the front of your body.

How many abdominal muscles exist?

The anatomy of your abdominal muscles comprises five pairs. Two of these are vertical (up and down) muscles located at the center of your body. The other three are flat muscles stacked on top of one another, found toward the sides of your trunk.

The two vertical muscles are:

Rectus abdominis: This pair of muscles runs down either side of the middle of your abdomen, extending from your ribs to the front of your pelvis. They are divided into two sections by a muscle known as the linea alba. The rectus abdominis functions to hold your internal organs in place and helps maintain stability during movements. When someone has a toned abdomen, their rectus abdominis can form visible bumps often referred to as a “six-pack.”

Pyramidalis: This small, triangular muscle is located at the base of your pubic bone. It is positioned in front of the rectus abdominis and attaches to the linea alba. The pyramidal helps regulate internal pressure in your abdomen. Approximately 20% of individuals do not possess pyramidal muscles.

The three flat muscles are:

- External obliques: These are a pair of muscles, one on each side of the rectus abdominis. They are the largest flat muscles, positioned at the bottom of the muscle stack. They extend from the sides of the body toward the center. The external obliques enable your trunk to twist from side to side.

- Internal obliques: Located on top of the external obliques, the internal obliques are a pair of thinner and smaller muscles just inside the hip bones. Like the external obliques, these muscles run from the sides of your trunk toward the center. They work in coordination with the external oblique muscles to allow the trunk to twist and rotate.

- Transversus abdominis: The deepest of the flat muscles layered above the internal obliques, the transversus abdominis aids in stabilizing your trunk and maintaining internal abdominal pressure.

- Surgical Considerations

- The abdomen is clinically segmented into nine areas, which are defined by two vertical sagittal planes extending from the midclavicular to the mid-inguinal lines, as well as two horizontal transverse planes, one located at the subcostal line and the other at the iliac tubercles. The umbilicus is positioned at the center of these nine regions. The specific regions and their respective organs are described below:

- Right hypochondrium: liver, gallbladder

- Epigastrium: stomach, liver, pancreas, duodenum, adrenal glands

- Left hypochondrium: spleen, colon, pancreas

- Right lumbar region: ascending colon, right kidney

- Umbilical region: navel, small intestine

- Left lumbar region: descending colon, left kidney

- Right iliac fossa: appendix, cecum

- Hypogastric: female reproductive organs, sigmoid colon, including bladder

- Left iliac fossa: descending colon, sigmoid colon

From a surgical standpoint, the portal triad contained within the hepatoduodenal ligament holds significant importance, consisting of the proper hepatic artery, common bile duct, and portal vein. The Pringle maneuver involves applying pressure to this ligament to manage hemorrhage.

What are the 9 abdominal regions?

The abdomen can be categorized into nine distinct regions based on their anatomical locations. These regions include the right and left hypochondriac areas and the epigastric area, which are situated in the upper abdomen. The middle abdomen comprises the right and left lumbar regions as well as the umbilical region. The lower abdomen is made up of the right and left iliac regions and the hypogastric region.

Why is it crucial to understand the nine abdominal regions?

Familiarity with the various anatomical regions of the abdomen is essential in any field that necessitates quick identification of problematic areas and their related organs. For instance, if a patient reports experiencing severe pain in the right iliac region, it could potentially be related to the appendix.

Principle: Two vertical midclavicular lines (left and right) intersect two horizontal planes: the subcostal plane (which goes through the lower edge of the 10th costal cartilage) and the trans tubercular plane (which runs through the tubercles of the iliac crests), creating nine segments: right and left hypochondrium, epigastrium, right and left lumbar regions, umbilical region, right and left inguinal regions, and hypogastrium.

Segments:

The upper abdomen consists of the (1) right hypochondriac, (2) epigastric, and (3) left hypochondriac regions.

The middle abdomen includes the (4) right lumbar, (5) umbilical region, and (6) left lumbar regions.

The (7) right iliac, (8) hypogastric, and (9) left iliac areas are located in the lower abdomen.

Divisions and landmarks

Although the nine-region system may seem more complex compared to the four-region scheme, it aids in more precisely localizing clinical symptoms and achieving an accurate diagnosis more swiftly. This scheme utilizes two vertical planes and two horizontal planes to delineate the nine segments. The vertical planes are referred to as the left and right midclavicular lines, which extend from the midpoint of the clavicle downward toward the midpoint of the inguinal ligament.

The transtubercular and subcostal planes are the horizontal planes. The subcostal plane runs horizontally through the lower edge of the tenth costal cartilage on both sides. The transtubercular plane crosses through the tubercles of the iliac crests and the body of the fifth lumbar vertebra.

The right and left hypochondriac regions are located superiorly on either side of the abdomen, while the epigastric region is centrally positioned between them at the top. Surrounding the umbilical region, which is at the center and features the umbilicus as its focal point, are the right and left lumbar regions. Finally, the right and left inguinal regions are found at the bottom on either side of the hypogastric region, which is the lowest in the central line of segments.

Each of the nine regions will now be listed individually from left to right in a craniocaudal order:

Left hypochondriac region

The left hypochondriac region includes the:

- stomach

- upper section of the left lobe of the liver

- left kidney

- spleen

- tail end of the pancreas

- sections of the small intestine

- transverse colon

- descending colon

Right hypochondriac region

The right hypochondriac region comprises the:

- liver

- gallbladder

- small intestine

- ascending colon

- transverse colon

- right kidney

Epigastric region

The epigastric region consists of the:

- esophagus

- stomach

- liver

- spleen

- pancreas

- right and left kidneys

- right and left ureters

- right and left adrenal glands

- small intestine

- transverse colon

The location of the transverse colon can vary slightly among individuals due to its mobile attachment within the transverse mesocolon. Typically, it is situated between the epigastric and umbilical regions of the abdomen.

Left lateral/lumbar region

The left lateral region contains a:

- portion of the small intestine

- segment of the descending colon

- part of the left kidney

Right lateral/umbilical region

The right lateral region holds the:

- inferior portion of the liver’s right lobe

- gallbladder

- small intestine

- ascending colon

- part of the right kidney

Umbilical region

The umbilical region is made up of the:

- stomach

- pancreas

- small intestine

- transverse colon

- medial ends of the lower poles of the right and left kidneys

- right and left ureters

- cisterna chyli

Left inguinal region

The left inguinal region comprises the:

- descending colon

- sigmoid colon

- segment of the small intestine

- left ovary and left uterine tube (female)

Right inguinal region

The right inguinal region includes the:

- small intestine

- vermiform appendix

- cecum

- ascending colon

- right ovary and right uterine tube (female)

Hypogastric region

The hypogastric region consists of the:

- small intestine

- sigmoid colon

- rectum

- urinary bladder

- right and left ureters

- uterus, right and left ovaries, and uterine tubes (female)

- ductus deferens, seminal vesicles, and prostate (male)

The four region scheme

The four region scheme

Divisions and landmarks

The four anatomical regions of the abdomen are identified as quadrants. They are divided by theoretical anatomical lines that can be traced on the abdomen using specific anatomical markers. The median plane follows the linea alba and stretches from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis, vertically dividing the abdomen in half. The transumbilical plane is a horizontal line located at the level of the umbilicus. These two planes intersect at the umbilicus, forming a cross pattern and splitting the abdomen into four quadrants.

Right upper quadrant

The right upper quadrant (RUQ), in a craniocaudal sequence, encompasses the:

- the right lobe of the liver

- gallbladder

- pylorus of the stomach

- first three sections of the duodenum

- head of the pancreas

- right kidney and right adrenal gland

- distal ascending colon

- hepatic flexure of the colon

- the right half of the transverse colon

Right lower quadrant

The right lower quadrant (RLQ) contains the:

- majority of the ileum

- cecum and vermiform appendix

- proximal ascending colon

- proximal right ureter

Left upper quadrant

The left upper quadrant (LUQ), in a craniocaudal order, consists of the:

- left lobe of the liver

- spleen

- stomach

- jejunum

- proximal ileum

- body and tail of the pancreas

- left kidney and left adrenal gland

- left half of the transverse colon

- splenic flexure of the colon

- upper section of the descending colon

Left lower quadrant

The left lower quadrant (LLQ) consists of:

the distal portion of the descending colon,

the sigmoid colon,

the left ureter.

Depending on a person’s sex, both the left and right lower quadrants may also contain parts of the urinary bladder and uterus (in females), as well as:

- the ovary and uterine tube (in females)

- the ductus deferens (in males).

Clinical Significance

Abdominal signs and symptoms can result from a variety of disease processes, such as:

vascular issues, infections, trauma, autoimmune disorders, musculoskeletal problems, idiopathic conditions, neoplastic growths, congenital abnormalities, and more. The information provided below is not meant to be an exhaustive list; instead, it should act as guidance for common pathologies in their respective quadrants, aiding in clinical decision-making, especially regarding imaging and surgical methods.

Right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain

This is generally associated with gastric reflux, gallbladder disorders, hepatitis, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, pyelonephritis, kidney stones, retrocecal appendicitis, or bowel obstructions.

Right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain

Frequent causes include appendicitis, Crohn’s disease, cecal diverticulitis, ectopic pregnancy, endometriosis, inguinal hernia, ischemic colitis, ovarian cysts, ovarian torsion, pelvic inflammatory disease, psoas abscess, testicular torsion, or kidney stones.

Left upper quadrant (LUQ) pain

Common reasons for pain in this area include gastric reflux, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, splenic infarction or rupture, pyelonephritis, bowel obstruction, or aortic dissection.

Left lower quadrant (LLQ) pain

Typical causes can be diverticulitis, kidney stones, pyelonephritis, ectopic pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, inguinal hernia, ovarian cysts, ovarian torsion, pelvic inflammatory disease, psoas abscess, testicular torsion, abdominal aortic aneurysm, irritable bowel syndrome, or small bowel obstructions.

Pectinate Line

The pectinate (dentate) line also has clinical significance. Above this line, one might expect internal hemorrhoids and adenocarcinoma; these internal hemorrhoids are usually not painful due to their visceral nerve supply. In contrast, below the pectinate line, you may find external hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and squamous cell carcinoma, with external hemorrhoids being painful because of their somatic nerve supply.

Inguinal Hernias

A hernia, defined as the protrusion of abdominal contents through an opening, can result in significant pain, incarceration, and the potential for strangulation. Direct and indirect inguinal hernias are also possible. The anatomical difference can be remembered with the mnemonic

“MDs don’t LIe.” If a hernia is positioned Medial to the epigastric blood vessels, it is categorized as a Direct inguinal hernia. Conversely, if the hernia is found Lateral to the epigastric blood vessels, it is an Indirect inguinal hernia.

Direct inguinal hernias, which usually occur in older males, are only surrounded by external spermatic fascia and pass through solely the external inguinal ring.

Indirect inguinal hernias extend through both the internal and external inguinal rings and have the potential to reach the scrotum. They are encased by all three layers of spermatic fascia: internal, cremasteric, and external.

Overview

The anatomy of the abdominal regions and planes comprises multiple layers, each with distinct blood supply and innervation. The abdomen has been divided into halves, thirds, and even as many as nine individual areas. The abdominal wall layers include the skin, superficial fascia, and muscles.

In human anatomy, the abdomen refers to the body cavity situated between the chest or thorax above and the pelvis below, extending from the spine at the back to the abdominal muscle wall at the front. The diaphragm serves as its upper limit. There is no definitive wall or clear separation between it and the pelvis. It houses the digestive organs and the spleen, which are enveloped by a serous membrane known as the peritoneum.

FAQs

Where is your abdomen specifically located?

The abdomen (commonly referred to as the belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front section of the torso situated between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and other vertebrates. The space taken up by the abdomen is called the abdominal cavity.

Where do people usually feel abdominal pain?

Abdominal pain refers to discomfort experienced anywhere from beneath your ribs to your pelvis. It is also commonly called tummy pain or stomach pain. The abdomen contains various organs, including the stomach, liver, pancreas, small and large intestines, as well as reproductive organs. Significant blood vessels are also present in the abdomen.

Where is a woman’s stomach located?

Stomach: Anatomy, Function, Diagram, Parts Of, Structure. The stomach is positioned in the upper part of the abdomen on the left side of the body. The top of the stomach connects to a valve known as the esophageal sphincter (a muscle at the end of your esophagus), while the bottom connects to the small intestine.

Where is gas pain typically felt?

Gas pain can occur in the abdomen, chest, or upper back regions. It may feel like a sense of pressure, bloating, or a dull ache.

What part of the body does the abdomen represent?

The abdomen is the section of the torso that lies between the thorax and the pelvis. Firm fixation of the tissues in a cadaver can sometimes make it challenging to differentiate between bony landmarks and well-fixed soft tissue structures.

References

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025, January 3). Peritoneum | abdominal cavity, mesothelium, serous membrane. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/peritoneum

Anatomy of the abdomen and groin. (n.d.). Saint Luke’s Health System. https://www.saintlukeskc.org/health-library/anatomy-abdomen-and-groin#:~:text=The%20belly%20(abdomen)%20is%20the,lowest%20part%20of%20the%20abdomen.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, February 2). Abdomen. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Abdomen (1st ed.). n.d.).https:/www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553104/https:/study.com/learn/lesson/regions-abdomen-overview-locations-nine.html

Abdominal muscles. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21755-abdominal-muscles

Regions and planes of the abdomen: overview, abdominal skin, superficial fascia. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1923166-overview?form=fpf